The Privilege of Grief

In the sea, a raging storm of untamed nature is giving birth. Winds growl and stampede for incalculable distances. The waves pirouette in harmony to the naked eye but with malice to those who know. Two men in a small boat are being thrown around with no say in how or where they move. One man, much older than the other, with gray hair and in a yellow raincoat, sits at the front of the boat. The other man, younger, in the same yellow raincoat but wearing a matching hat, sits at the end, tired and frightened by the fury of the Lord.

“How much longer? At this point, there’s no seeing it. It has to be gone by now!” the young man screams at the top of his lungs.

“No, no. It's still here. I know it is. He always said it was here… and when you’re ready, it would show itself,” says the old man in a calm voice. He stares out into the sea as the pitch black stares back into him, unwavering at his want.

The young man, frustrated, begins to say, “It’s not in there! We aren’t making any progress just going on like this.”

The old man, like a statue, holds his current position as if the words were never spoken out loud.

“You think it will really show itself at this point during this time? Really?” The young man screams again at the top of his lungs as his vocal cords reverberate.

The old man says quietly, “Yes.”

The young man looks at the old man with anger but understanding and then looks out at the sea in its fury and magnificence. The sea, the all-seeing eye, looks at them in their boat as if they are nothing more than particles, things so infinitesimal that their lives are not worth a thought. The old man, through his lack of expression and emotion, feels it all. The rain, the waves, the vastness, the young man—he feels it all. That is his conundrum: he feels in a way that the boy behind him could never try to understand. He feels so deeply, even when the leviathan itself warns him of its proximity. But nonetheless, he still feels, searching for it, looking for that solution, that truth, the thing that will make it all go away. Or at least the consolation of helping it all make sense, like any port in the storm.

In November of 2019, I came home from college, excited to see my family and talk about my new experiences and life the past ten weeks had shown me. I got on a plane in Boston, flew to Chicago with a layover, and then landed in Dayton. My father picked me up, and I got in the car after placing my luggage in the trunk. We drove and talked about football and school, as usual. During the drive back home, he told me my grandmother had passed away. Almost as a matter of fact, though no fault of his own, knowing him and knowing me, I would have said it the same way to my own son. Though funny enough, even to this day, it didn’t hit me. I said something along the lines of “oh” or “what happened,” and he explained it to me, but there was no breakdown crying, no shock response, nothing of the sort. And it bothered me, like it usually does. Shouldn’t I feel something? Shouldn’t this violent rage and anger, this abrupt sadness and grief, fill me, almost drown me from the constant flow? It’s a question I have always had and will continue to have, but with her, with my grandmother, with Granny, it bothered me the most. It was like a scratch I couldn’t reach, but it was more than that; it was like a question so vivid, so pronounced in my mind, worked out to perfection on the page, but the answer hid deep within the off-white, deeper in my mind, unimpressed and content with staying there. The first real emotion I had was when my mother told me while I was playing a game; I remember it. Dropping the controller, letting out tears. But still, I needed more; I wanted more from myself. It was as if my own reaction wasn’t sufficient for me; it wasn’t sufficient for what the world demands of me. What makes it so odd is that she was a woman after my own heart, the person I loved more than anyone, and I can say this truthfully. The woman who helped raise me, taught me to read, taught me about God, and helped shape the core of my being, the guiding moonlight that, almost like a trance, forces me to go on without question. How could the woman who did all of this for me in my life only get these few tears on a second reaction and then some more at her funeral? I was questioning myself then and now, thinking if anyone deserved my grief, my anguish, it was her and no one else. But she only received it to satisfaction. In this instance I felt closer to a stranger learning about the death of women I’ve never met rather than the grandson of one I’ve always known.

The Stranger is a novella written by Albert Camus, one of my favorite philosophers. The Stranger, much like a lot of Camus's work, deals with existentialism, but one of the focal points of the story is the main character, Meursault, and his feelings towards the death of his mother. “I summarized The Stranger a long time ago, with a remark I admit was highly paradoxical: ‘In our society, any man who does not weep at his mother’s funeral runs the risk of being sentenced to death.’ I only meant that the hero of my book is condemned because he does not play the game.” These are the words of Albert Camus about the book, and a somewhat basic summary of it. As the catalyst of the story, and what pervades throughout the reader's mind more than Meursault, is the death of his mother. This inciting incident is what, later down the line, is a factor in his sentencing to death. He has no emotion or reaction to the death of his own mother. No argument can be held to the fact that people, when someone dies, are overcome with great sadness and grief, as they should be, since someone they loved has just passed away. Though also, no real arguments can be held to the fact that, as Camus says, “any man who does not weep at his mother’s funeral runs the risk of being sentenced to death.” Obviously not literally, but being seen as something alien or abomination-like. We are supposed to cry and feel sadness and tell people that someone we loved has passed away, and then they tell us how sorry they are and offer us any help they can provide or someone to talk to. Though, and I may be outing myself here, but we know that most of this is hollow. I am not saying that this is always fake and people never want to help someone going through grief or that their sadness is not genuine. But what I am saying is that we would be remiss to think that society as a whole does not expect this of us as if we are bound to it from blood pacts at birth. This is how you react when someone dies; this is how you are supposed to carry yourself, this is what you are supposed to say to said person, and then you can move on to the next. A simple series of code: if this, then that. But I didn’t feel like this; I didn’t have immediate grief, and when the sadness came, it washed away quickly, like a wave falling to the beach and then inviting itself back to the sea. It was there for an instant and then gone again. So is there something wrong with me? I do not think so, or at least focusing on the topic at hand, I do not think so. When I go back and think now, maybe something else was washing over me. During that time I was completely focused on football and school given the rough term I had had before going home. I was stuck with pressures I placed on myself and expectations I had to surpass. During that period of time there was no room for anything else it would have only slowed me down. Although society wanted me to grieve in a certain way, I couldn’t and can’t, but still, I feel and felt that loss of Granny. In a weird way, I think as much as she was a foundation and part of me in life, physically and emotionally, spiritually and metaphorically, she made up meaning and purpose in my life also. When she died, it was almost as if the counterbalance threw off its equal sway. It was not the sadness that overcame me but the reality of who I am as a person that fell into question. It is sad to think that only now while writing this piece and discussing this topic that I find these realizations but I give Grace to my past self knowing what he was focused on and working through. This sounds selfish at first view, but I think this is true of all of us who lose someone close and important to us. They make up who we are, sometimes at a fundamental level. From what they taught us, the experiences we had with them, or even the small moments that we remember with them. It’s like the cracking of stone; a small fragment of us is gone, and we seldom know how to and cannot replace it.

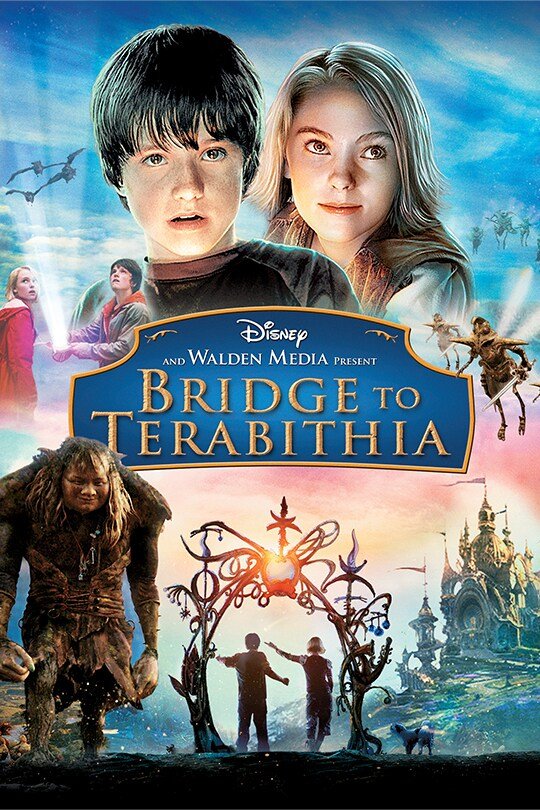

Bridge to Terabithia

In the movie Bridge to Terabithia, it follows a boy named Jesse and a girl who has just transferred into his middle school named Leslie. Both are on the fringe of middle school society, Jesse being introverted and Leslie being weird, respectively. Through this, they bond and create a genuine and honest friendship, helping each other not only navigate but sustain the woes of middle school pressure and bullying. From the outside, and with this basic synopsis, it seems like a simple Disney Channel movie that would get no real attention, just your average feel-good movie you watch and forget. Although the simple analysis in no way gives it the credit it deserves for being one of the more complex and honest Disney Channel movies there is. From the effects of home life to the nature and nurture conversations and the effects they have on children, not only in who they are but their beliefs and religion, while at the same time showing the beauty of childhood intertwined with its abrasive desolation in the eyes of our youth. A movie worth watching and a more in-depth review, but what is more important is what happens towards the conclusion of the movie. Leslie has a vivid imagination, most likely because of her parents, but she does not equate it as such. She brings Jesse around to have the same vivid imagination, leading them to create the fictional forest of Terabithia. Every day after school, they go to Terabithia to talk and continue their adventures, but it’s there where both of them discuss their troubles at school and home and lean on each other to create a genuine bond. It eventually leads them to both become deeply entrenched in each other’s lives. One day, instead of going to Terabithia, Jesse decides to go on a field trip with his teacher to a museum, and Leslie goes to Terabithia by herself. As Jesse comes back home, he learns that while trying to swing across on the rope, it broke, and Leslie likely hit her head. Leslie died. The impact and surprise of this scene as a kid cannot be overstated. For something like this to happen in a children’s movie, a Disney movie no less, is surprising, to say the least. But the purpose of it is its impact on Jesse. He denies it at first, does not believe it, takes his anger out on those around him, even his younger sister who wants to go to Terabithia, but he pushes her down and exclaims, “It’s our place!” Leslie, as much of a friend as she was to Jesse, brought significant and profound meaning to his life. It was not just her birthday gift, friendship, advice, help, or all the other support that she brought to Jesse, but it was a combination of the group, the whole, that brought meaning to his life. Jesse, before Leslie, had no friends, was bullied, and felt as an other in his own home. Though when Leslie came into his life, she significantly and forever changed it to its core. She brought meaning to it. Not meaning in the superficial sense but meaning in the hyper-cardinal sense. Leslie showed him what friendship was, what you could think of not only on the page to draw but just through your mind and thinking and thinking so vividly and intensely to overlay it on reality itself. She encouraged him to be excited to see her, but in turn to go to school every day and spend countless hours in a forest existing with each other. Leslie, in a way even deeper than this explanation, brought meaning to his life that only Jesse, that imagined character, that name on a script portrayed by an actor, could only ever understand. It is something so lucid, so arresting, that it is hard to explain. As if having a piece of yourself ripped from your very being. Like a man wandering aimlessly with no soul and a broken heart, with amnesia blackening his sight, only knowing that he has lost something but what he can no longer remember. It is something so abrasive, so significant, that you can only understand it when you have felt it. When a man or woman has felt death cross the door, not to claim its prey but to tell it in a subtle way that it has been ensnared in a trap that has held many and claimed many before it.

“There is no love of life without despair of life,” words from Albert Camus, but as they are targeted towards oneself, they can also be directed towards the situation of loss and its abbreviated totality. As we have seen, loss, despair, and grief are pieces of a greater whole. They are, in their own sense, a reaction or alarm to the self and the soul when one’s meaning is in conflict with the passing of another. With Bridge to Terabithia, it was Leslie, and with myself, it was my grandmother. Though despair is not just a state of limbo waiting to be freed to move on past this void, it is a state of enlightenment to enhance and challenge both parts of yourself in order to claw out of the darkness. Søren Kierkegaard, a Danish philosopher of the 19th century, speaks deeply about this topic in his book The Sickness unto Death. He explains that the self and spirit are one and the same, and that despair is what infects them. Despair creates a rift within the self, disrupting its harmony. As he states, "a human being is a synthesis of the infinite and the finite, of the temporal and the eternal, of freedom and necessity." Despair disrupts this synthesis, causing an imbalance. Despite this, despair is a constant and unrelenting presence in our lives. Kierkegaard suggests that we are always despairing over something, whether big or small; in this case, it is the loss of another. Essentially, we are not trying to rid ourselves of despair directly, but rather to rid ourselves of a part of our identity. However, this is impossible. In this context, Leslie's passing leads Jesse to anguish and a desire to eliminate his despair, which is actually a meaningful part of himself because of her. Kierkegaard asserts that the person we lost becomes an integral part of us, eternally intertwined within our being.

Kierkegaard explains the power of despair beautifully, with words and thoughts that almost place it into reality itself. However, the "almost" should be emphasized, because until you truly feel it—that grief, that despair, that sadness—you can never feel those words or thoughts to their truest extent. As I think about her now, after the research and all the time spent in preparation of this piece, I feel closer than before in a way that seems foreign to me. The time spent has been profound in understanding how much my grandmother has meant to my life, and even more so than before, how much she still empowers me today. Not only through my thoughts and actions or the memories I now carry alone but also through the emotions and the spiritual connection that has been rediscovered. Not that it left, but what was once in the shadows now bathes in the light. She is a part of my every being and what makes up the whole of me. The only part that I regret is how long it took—how much time and effort I needed to spend to realize this. Though now, on the other side, time was the answer, the only path that could bring me to this point.

A Ghost Story

A Ghost Story is likely a weird film for most people who watch it. A man moves into a new place with his girlfriend. He then suddenly dies, becomes a ghost, and haunts the house. The movie follows him and the house as people come and go, with time moving forward and backward. At first, it's comical seeing Casey Affleck with a bedsheet over his head, eyes cut out like some fourth-grade rendition of a ghost play. However, as you watch the movie and consider it from different angles, you realize that it’s not just about grief, loss, and moving on. It's also about what we leave behind when we’re gone and what people take with them that was once a part of us. This applies not only to our loved ones but to all the people who pass through our lives.

We often view things in a linear and focused fashion, forgetting the sweeping vista that is life. When Casey Affleck's character dies, we see his girlfriend go on with her days in mourning and sadness in a house she never liked. She goes through the stages of grief, packs up, and eventually leaves. While his ghost remains in the house, the part of him that brought her meaning and now constitutes part of her being goes with her. Other families move in and out, and eventually, the house becomes an office in a future far beyond our imagination. The movie also travels back in time to settlers on the land who build a house, only to be killed by Native Americans, marking the start of something new.

A Ghost Story presents limbo—or at least, that's what it seems if we simply stare at the bedsheet. It represents the inability to reach the gates of heaven and the lack of consequences to pass through the city of woe. It is eternal contemplation, eternal waiting, as we watch life pass us by. But when you look beyond the bedsheet, into the abyss it safeguards, you see it for what it truly is. It's not limbo, but the realization that we do not simply despair alone. We do not lead lives isolated to ourselves; our lives are made up of things, people, and times that span far greater periods than we can ever imagine. We are the synthesis of the infinite and finite, the temporal and the eternal, the freedom and the necessity. We are made up of everything that has come before us and will be a part of everything that comes after.

When I lost my grandmother, I came into conflict with my own being. Despite the pain, I realized how much she left of herself in my life. How I read, live spiritually, the words I don’t say to myself, the sayings I continue to use, and the mantra that has taken me this far in life—all of this is her. When someone passes, their meaning to us is more than a feeling; it is truly a part of our whole. It is what makes us, us. It is important to remember that as much as this part of us seems in conflict with the greater whole, like a body attacking a sickness, we must remember what was given to heal ourselves. It is like a symbiote, but in the relationship of two beings that need each other to survive and live on. Just as the self is a foundation to our structure, so are those who came before us and made us who we are. Who are we to say we are complete and whole beings outright? That we are individuals with our own thoughts and beliefs? The same can be said of the symbiotic relationship we hold with the past and with those who are no longer with us. The things they have instilled, the words they have said, the actions they committed, the achievements they received, and the battles they lost—all of it is a part of us.

In the movie, Casey Affleck’s girlfriend has a history of moving a lot. Every time she moves, she leaves a note behind in every house, inside the wall, to prove she was once there. This is one of the things that keeps Affleck’s ghost in the house, trying to read what the note says. As much as A Ghost Story is about Affleck’s ghost, it is much more about the house and the land, which have told many stories before him and will continue to tell more after him. It is made up not of the walls that enclose it from the outside world, but of the world that has given it its meaning, its story, proving to the world that it existed for a time.

The funny thing is, much like those settlers whose bodies fertilized the soil, the man who lost his life and became a ghost, the families who would move after him, and the office and city that would later usurp them all, time was the common factor. It has taken almost five years to realize all of this, but now I don’t regret the time it took. Time is enormous—far bigger and greater than any human can understand. It expands and flows in ways we can only theorize. However, like that ghost, it takes time to accept death and the hunter for their deeds. I don’t think I ever fought her death or was burdened by it, but I felt as though there was so much I wish she could have seen, so much we could have talked about, so much that was left for us to do. Now I think I still feel those thoughts and emotions, but not nearly to the same extent. I have accepted it; it is past me now. So much has changed and is continuing to change. I need not stay that same boy who lives with that pain and sorrow, as time has passed and so too shall I.As the house was turned into a metropolitan city, I too have now understood the beauty of her life and what it all means to me, and it will continue to become my very being. It took time to find this version of myself, to find this closure, to see my grandmother as I see her today. I know now that it will take more time to discover even more about her and myself, but the funny thing about life is that in its beauty, love, and grandeur, there resides malice in its anarchy.

The Stanger by Albert Camus

The Stranger is a book about relationships and a man who lacks or more precisely chooses not to find depth in any of his relationships, including the one with his mother. This ultimately leads to his execution. However, the story of Meursault, the main character, and the words written by Albert Camus are much more absorbing than just that. While it talks about relationships, its main focus, like much of Camus’ work, is the absurdity of life and its inherent meaninglessness. We often feel as human beings that we are owed something, that we deserve some semblance of recognition for life itself. But in the absurdity of existence, we are owed nothing because we are little more than anything. We are infinitesimally small beings compared to the vastness of space. As much as we find our lives of great importance, we lack the clarity of how small they really are, of how little we deserve to have a voice or an opinion.

A somewhat long explanation of absurdity is crucial when looking at The Stranger through this lens and as a greater piece. So a somewhat long explanation shall be given. Meursault seems strange, as the book implies. His relationships are surface-level at best, he does not follow societal standards in how he lives or thinks about life, and he views life with indifference and passivity. It is all chance, interchangeable, meaningless, and absurd. The world is simply a facade we hold on our shoulders. We believe that all the weight we bear must have meaning, that there must be purpose. If so, why must we all take Atlas’s mantle and suffer as we do? This is why we create notions of ambition, laws, and love. They are algorithms we follow, created by those before us who could not fathom the frenzy that comes with the enlightenment of the gospel truth. But for the few of us, the plaster begins to fade, the wallpaper crumbles from the sickness of age, and we see it: the randomness of life, the lack of true form it holds, flowing and convulsing, giving flagitious kisses to our accomplishments and reverent hands to our poisons.

Life has no meaning, and what we choose to do or not do has no meaning or point. It is all interchangeable. As Meursault says, “one life is as good as another”. When we create our laws telling us what is wrong or right, correct or not, we place order where there is none. We create roads where they don't belong. When a man who realizes this comes along, he is seen as an outcast, one who is not like us. Meursault loses his trial and hears the footsteps of the hunter approaching. He finds that all his efforts to evade the predator were in vain, like the rules and laws we create. It is all still meaningless. He embraces the inevitability, understanding that you cannot escape, especially the hunter. As his footsteps slow and he lines up his shot, when it connects and our body begins to turn cold, nothing mattered, and no one ever really cared.

Manchester By the Sea

Manchester by the Sea is a film about dealing with loss. Unlike the other films on this list, it does not focus on any singular event dealing with loss and the death of someone. The inciting incident is Lee Chandler losing his brother and having to go back to Maine to decide the family's future and what will happen with his nephew. Though all characters are affected by Joe Chandler’s death, there are many different forms of loss present throughout the film. From the boat that has been a part of the family, the loss of structure for Joe’s son Patrick, Patrick’s absent mother, and the sheer absence of any hope in dealing with all these situations.

What makes Manchester by the Sea a great film is that it depicts loss in its truest form. Not only how it affects us initially but how it has an everlasting hold over us, like a man haunted eternally. Loss does not simply go away; it stays with us and seeps into our very being. It straps us to a chair, forcing us to watch a tape that ever rewinds and plays. The perfect example of this in the film is Lee’s loss of his children. They died many years before Joe’s death, but as one could imagine, it has stuck with him ever since, leading him to move away from his hometown and lose his marriage. Grief and anguish are sometimes tattooed upon us, never leaving our sight. Just when we forget about it or think it isn’t there, it flashes itself again to show us it is still waiting.

Lee deals not only with his brother’s death but the death of his children throughout the whole movie. It seems as though the death of his children has a greater impact compared to his brother’s. When he first sees his brother dead in the hospital, there are no emotions expressed. This lack of emotion persists throughout the film. “I can’t beat it,” a simple line but the strongest and most important one from the movie, is said by Lee towards the end. It’s him finally admitting aloud that his grief, anguish, and depression can’t be stopped. He is losing the battle, and there isn’t a way to fight it.

What I love about the film is that as much as we think we can fight our circumstances and overcome them, the world does not conform to our desires. The world does not bend to our wants or needs. The world does not cooperate with our schemes or deviate from its path for our will. The world has no order; it is all chaotic and left up to forces that care nothing for our matters. As Lee wishes to rid himself of the weight of his children’s deaths, it stays with him. As he wishes to place Patrick in a great situation, he can’t. We can’t beat it. As much as we try to find meaning in the death of our loved ones and their impact on our lives, there is no guarantee it will be there when we look. That is, if we even have time to find it. We are guaranteed nothing, and ultimately, the pursuit and attempt at understanding the significance of someone’s life is a blessing in and of itself. As we walk through life, we believe we are destined to be winners, that somehow we are above those around us. But the house always wins.

I now know what my grandmother means and has meant to me, and I will continue to explore and find it even further down the line. Life, in its enormity, gives us that blessing, although it is not one given to the masses. Like Lee and many other real human beings, not everyone is given the ability to find it—to find that beauty, that serenity in death. Some can only cry at the funeral and proceed to work; others can only force their anguish and then return to life as it beckons them back. Only a few are able to find the esoteric knowledge that grief clutches with its withered hands. I am now able to consume the insights of such knowledge, but not long ago I was like many others, on the other side of such a door. Even in my separation from this comprehension, I was closer than many more people who are still behind the door. Most can only think of the price of the headstone on which the name is etched, or the body placed inside the casket, rather than the being of the person who has touched their life. Like myself, it may take time, but the truth may be that rather than a door separating the two sides, it is much closer to a barricade fortified to such an extent that not even time itself can erode its walls.

As I was thinking about this topic and writing it, I felt as though I was crafting a solid argument and answer to a question. With all the background research, especially a paper written by Michael Cholbi complementing the argument well, it seemed like a foolproof plan. Though the original title that came before any words were written still lingered in the back of my head: “The Privilege of Grief.”

I know it doesn’t make sense at first glance. How can grief be a privilege? This piece explains this question and the initial title. Most of us are not given the ability to go through the process of realizing how a person brought meaning to our lives or why they were so important to us. Life often stays in front of us instead of moving to the foreground. In most cases, we are not afforded the time or effort to process our emotions and feelings after a death; we simply must move on. It's always present within us, but we are told to press forward and let sleeping dogs lie.

When we discuss the privilege of grief, its importance lies in how the privilege forms. It is not something inherent, given because of status or wealth, nor determined by culture. It develops as the ability to be free—not in some grandiose sense, but truly free. Free time, time to spare, to take off, to be available, to decompress, to sit with yourself and work through the situation. What sparked this title and question is that in my own life and those around me, I have found this privilege absent. When someone dies in my family, it is always the same: the person passes away, everyone is informed, we go to the funeral, the gravesite, and then we go home and get on with our lives. Since a young age, I was always told to let them go. When someone dies, make your peace, go to the funeral, express your emotions, and then move on because they are gone now.

I wouldn’t say I disagree with this sentiment because I think moving on is best when someone dies. Cherish the memories you had together, but why linger for so long? When someone passes on to a better place, why be sad or melancholic? Though I agree with this sentiment, I also find it could have be created and done through necessity. From what I understand, my family and some others, specifically black people, follow the same heuristic. It may not be told the same way, but when someone dies, we move on. This is not to say that sadness is not experienced or expressed but more so the conscious and psychological parts of grief are what have been shaved. This is for many reasons specific to black culture and death, but the point is that time is of the essence. We do not have time to take away from work to sit with ourselves and contemplate. There is so much we must do that realizing the importance of a loved one’s life and how they became a part of our being is not something we can afford to do.

You might say that such reflection is easy and can be done in off time, but I would argue it is harder and takes more commitment and time than we would care to admit because it is our privilege. I myself have never really sat down and thought about my grandmother’s death in such a way until writing this piece. I have been a part of both sides in a way so to speak. It has taken me almost five years to get to this point to truly process her death and what she means to me and how it has impacted me on a far deeper level. In those previous years I had no time and took none to think about it. I was working and focusing on school and football to graduate early and palace myself in position to be successful. However now in Colorado I am still focusing on such things but have much more time than I previously did to place my mind in such a space. It's not that her death lacked importance, but in my case, obsession and focus took priority—an obsession and focus she instilled in me. For others, there are more pressing real-world causes that keep them from realizing their anguish, such as work, paying bills, taking care of children, home life problems, and other woes. This is what makes grief a privilege: the ability to sit with it and understand it, which the rest of us simply cannot afford. For every death in one's life, big or small, impactful or not, people struggle to even pay for the funeral to bury their loved one. It is watching those around you continuously work and set aside their sorrow for your betterment.

Black people are my focus when it comes to this question because it is who I am and what I know. As I watch and understand how other people deal with grief, loss, and death, I cannot help but see it through the eyes that I possess. It is also important to state that this focus is not correlated with the entirety of black people. As it is not a monolith and many black of many cultures experience and process grief in a variety of ways. As I continue it is through the lens of a lower socioeconomic status and background and that of the African American. Though still even with that preface I would say that these things have been instilled in all black people not just those with harder financial struggles. It shall be looked at later but even the specification has some overflow into the generalization.

When dealing with the question of whether there is privilege in grief, I cannot help but look at death itself. As we all know, black people deal with death at a higher rate and greater occurrence than any other group no matter the economic standing. We even announce death in a way that seems foreign to other people, at least from my experience. “Did you hear that so and so died?” is a phrase I have heard countless times throughout my life. It can be about distant relatives, friends, or acquaintances. This phrase announces death so matter-of-factly, diminishing the importance and effect of it that I have taken so long to describe. But to that same point, death surrounds African Americans in a way unlike any other group of people. I would be remiss and at fault if I did not examine how death affects black people. For us, death is no unforeseen plague or sudden occurrence. It is only surprising in terms of who it happens to and when. Otherwise, it is much like a hunter, not hidden but rather out in the open, standing in the streets, following its prey closely.

“Black Americans die at higher rates than white Americans at nearly every age” is the first sentence from the article “The Black Mortality Gap, and a Century-Old Document.” This section is foundational when facing the title “The Privilege of Grief.” At the time of the piece in 2021, the most recent mortality data showed over 62,000 deaths, which is 1 out of every 5 African American deaths. The group most affected by this inequality is babies, with African American babies being more than twice as likely to die before their first birthday compared to white babies. Though alarming, this mortality disparity has been a problem within the African American community since we came to America. Racism profoundly affects health determinants such as lower levels of income and generational wealth, less access to healthy food, water, and public spaces, environmental damage, over-policing, disproportionate incarceration, and more. Any problem that plagues America is much worse for Black Americans. For instance, Black Americans receive less and lower-quality care for conditions like cancer, heart problems, pain management, prenatal and maternal health, and overall preventive health. The pandemic worsened all of this by a wide margin. This section's importance lies in understanding why and how these disparities exist, leading us to the Flexner Report.

Abraham Flexner

In the 1900s, the medical field was out of control. Students weren’t being taught well, lacked the necessary education, and many unqualified doctors were practicing. Abraham Flexner aimed to change this. He proposed many changes, such as raising pre-medical entry requirements and partnering with hospitals. The effects were remarkable, with many schools closing, the field gaining scientific rigor and status, and doctors becoming more qualified, leading to greater patient protection. However, the flip side of this coin was its effect on black people in the medical field. Black people already faced segregated care, black medical students were excluded from training programs, and black physicians lacked resources for their practice. The new standards from the Flexner Report, though beneficial, were detrimental to black people. After the report, only two schools accepted African Americans, and white institutions did not. The report explicitly recommended that black doctors only see black patients and focus on hygiene since everything else would be too dangerous for them. It advised white doctors to offer care to black people to prevent disease transmission to white people. While the report seemed beneficial, it increased exclusivity, reducing racial presence and class diversity.

Change, disparity, and exclusivity are often disguised as improvement. Groups like the American Medical Association (AMA) and Flexner worked to increase the number of elite white physicians, eliminating those who offered lower or free care, often black people. These standards and systemic norms persist today, with the AMA opposing publicly funded programs that could harm physician earnings. This greatly affects black people, who are disproportionately impacted by all these issues. Lower reimbursement rates discourage doctors from accepting Medicaid patients. Many states, mostly in the South, have not expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act. Doctors such as plastic surgeons or orthopedists make far more money than pediatricians, public health doctors, and prevention doctors, who deal with conditions like heart disease and diabetes that disproportionately affect black people.

To further compound this issue, we must consider necropolitics. Necropolitics is the use of political and social power to dictate how people live or die. Achille Mbembe and Subhabrata Bobby Banerjee expanded on this term. Mbembe, in his book Necropolitics, presents a vast understanding of the term and its historical presence. Necropolitics depends on many functions, but I will focus on the state of siege and sovereignty. The state of siege, as described by Mbembe, gives the state the ability to perform systematic and structured oppression and killing, distinguishing neither internal nor external enemies. Sovereignty, while more obvious, is equally expanded by Mbembe. He states that in necropolitics, sovereignty rests on the belief that the subject is both master and controlling author of their own meaning. It involves self-institution and self-limitation. Sovereignty, in the context of necropolitics, is “the generalized instrumentalization of human existence and the material destruction of human bodies and populations.” The state of siege powers necropolitics, and sovereignty determines the roles of each actor, from the policed and subjugated to those who determine the form of oppression.

Necropoltics by Acheille Mbembe

Another important term in this discussion is biopower, coined by Michel Foucault, which refers to the literal power over bodies. This concept relates to necropolitics, and racism enhances it. Foucault directly states, “that old sovereign right to kill.” Racism’s function is not simple malevolence but systemic regulation and distribution of death to further oppression and the state of siege. We now see how death, racism, oppression, and black people are interconnected. It is not just being surrounded by death through happenstance or random occurrence but systemic, structured, and institutionalized functions. It involves food deserts, lack of healthy foods, over-policing, mass incarceration, lack of funding and support for underprivileged communities, and more. In its most complete and disturbing form, this resembles the Nazi state, which made the management, protection, and cultivation of life coextensive with the sovereign right to kill. Though this is its worst form, it has become more mechanized and sophisticated.

Necropolitics, while a fairly recent term, has been present since time immemorial. It is evident throughout history, particularly during colonization and imperialism, where states obtained resources and oppressed people, becoming the sovereign power determining life and death. This has happened throughout history and persists today in different forms. Mbembe notes that mechanization and industrial development have made these processes much more “technical, impersonal, silent, and rapid.” Racist stereotypes and class-based racism have aided this. Higher and lower people are distinguished, with the latter deemed sacrificial. The most violent form was Nazi Germany, but slavery in the United States also exemplifies this. African slaves were used as commodities and tools rather than people, their value determined by their productivity. Under colonial rule, peace was presented as the constant state, though it was closer to endless war perpetuated by racism and the view of oppressed people as savages. Mbembe says these zones are seen as impossible to end in peace, so war and disorder persist indefinitely for the state’s needs, presenting an absolute good versus absolute evil.

A modern example of necropolitics is the occupation of Gaza and the West Bank in the Palestinian-Israeli conflict. Territorial fragmentation halts movement, placing boundaries and increasing the sovereign's power compared to the oppressed. Mbembe describes vertical sovereignty, where the sovereign literally places themselves above the oppressed, using helicopters to police the air and bulldozers to intimidate. This example illustrates the presence of disciplinary, biopolitical, and necropolitical power. In the United States, black neighborhoods are over-policed and lack basic needs, creating a cycle of violence and crime that leads to more policing and incarceration.

Lastly, necrocapitalism, expanded upon by Subhabrata Bobby Banerjee, involves gaining wealth through death and violence. It requires spaces of exception where individuals lack rights, such as concentration camps, colonized African countries, Gaza, or low socioeconomic U.S. neighborhoods. Deprived of autonomy, increased policing, and limited movement, people in these spaces represent the homo sacer, individuals whose lives were seen to have no value to the gods thus not being able to be sacrificed, but in the same instance can be killed because they hold no value to society. Our economy, built on death and suffering, depends on this death to increase profit. The best example to explain is found In the film Snowpiercer. In the film the world has ended and all of humanity is placed on a train. It is divided into sections with the poor people placed at the tail end and the wealthier inhabitants placed in the front. Those at the tail end try a revolt and face heavy casualties throughout the movie. The tail-end passengers live in squalor and are readily killed for population control, representing the homo sacer. Though this killing was not just because of the revolt but was planned and intentionally orchestrated.

Massacre of the Innocents by Peter Paul Rubens

Understanding necropolitics and necrocapitalism, we see that death presents itself as an ever-looming cloud over African Americans more than any other race. Healthcare is an uphill battle, and death is a regular occurrence, baked into everyday life through systemic pressures, lack of support, and policing. These compounded issues and detrimental healthcare highlight why grief, in this sense and when considering black people, is a privilege.

Though I make this claim, I acknowledge that not everything is bad. When it comes to the black experience, death is dealt with in many unique ways. Black people do experience grief, facing it regularly and dealing with it differently. And we do have the ability to find great realization from it. Again there is no monolith in how grief is experienced or faced; it is complicated and different. For example, Although the initial experience with grief might be unique, black funerals often serve as celebrations of life. Religion also plays a significant role in this perception, A topic That deserves much more room to be discussed, with some black people relying on their relationship with God rather than healthcare. Funerals are seen as a celebration because the person is believed to be going to a better place. This view, while it does not eliminate sadness, often rids us of prolonged grief. Why be sad when someone is enjoying their life in heaven with God? Why be tormented when they are moving to a better place, especially compared to the life they lived here? This is a sentiment and belief that has helped me and been instilled in my family also. Since why hold on to someone who is going to a better place? It is one that places life and everything into a much needed perspective during a time of sadness.

I will present a rebuttal to my concessions, however. Although this is through the lens of African Americans, particularly those from a lower socioeconomic background, it looms over more than any other facet of Black people. I will not fully concede to the notion that those of higher socioeconomic statuses do not face it. Given our history in this country, it is rare to find an African American who has been wealthy across generations. To simplify the argument and give some tin man support, it makes sense to say that given their wealth—and, as I have said, the freedom that comes with it—they are able to process grief on a conscious psychological level that I assert Black people cannot. They are in a perfect position to do such things, even better than me here in Colorado. And to further support it need not even be wealthy black people but comfortable or middle class black people who are in the same boat as the wealthy group. However, when we examine the argument more critically and in the straw man light, as I stated earlier, it begins to edge closer to generalization. We know there are wealthy Black people, yes. Yet we can also say that there are even fewer who have been wealthy for many generations. They would grow up with these notions of handling grief given it was an upward climb of the economic ladder, usually a steep one at that. From this, some have become better at processing grief, but I would argue that very few undergo such shifts.

Old habits die hard, and even wealthy African Americans are still, without a doubt, African Americans in the eyes of the world. The statistics, death rates, and systemic problems do not overlook them. And when looking at those same comfortable or middle class black people they face these challenges even more so given their close proximity and lower level of wealth. To add to this—and perhaps for a piece down the line—many Black people who become rich still possess a compulsive desire to work and continue growing their wealth. Whether they fear losing it or feel the need to further set up their families, this drive never leaves. This is another generalization, but one many people have heard from wealthy African Americans and one that is hard to disprove. These factors place our wealthy counterparts in similar circumstances, do they not? Just in a brighter but still dim light. And this is without mentioning the pervasive masculinity challenges in the Black community. Many young boys have been told to be strong and never cry because that is not something a man does. They carry these words from childhood to adulthood and pass them to their children. Those same little boys look at us in the mirror, holding back torrents of tears. This problem is not beneficial, but like most things, I believe it was created out of necessity for facing much greater, more violent challenges. Sadly, it still lingers today and manifests as a part of shutting down the process of grief. This rebuttal to my own concession is lengthy, but it goes to say that while this is a problem of the lower class, those who are rich are not unbound by it. Even more so, as they walk as freed men and women, they are as chained like the rest of us to the immovable boulder; they are just placed on a floor above.

Manitou Incline

I recently did the Manitou Incline in Colorado. It is 0.88 miles with 2,700 steps of varying degrees and a 2,000-foot elevation gain—a monster of a hike. The first few hundred steps seemed fine, but around the 500 mark, you start to feel it. You want to keep going, but your legs beg you to stop. I realized, why finish the hike while stopping as few times as possible? How many chances will I have to see a view like this, and how many people will never see it? It was beautiful. So I stopped many times to take pictures and be present. Along the way, I met many different people taking the same journey. I even stopped to talk to a couple of people, learning a small piece of their story and being offered some gum. As arduous as the hike was, there was no point in finishing it fast. I am happy I took my time because I appreciated the experience and met many people along the way. Through the hike and reaching the top, I realized grief is no different. It is something that some people encounter and others do not. Some take different stances on it, follow different plans and ideas of how to handle it. Others rush through it or never address it. Then there are those who take their time to face it, look into the cold nothingness of it all, and say to the unrelenting force, “I am here to move with you.” Grief is a struggle, without a doubt. It is 2,700 steps of varying degrees, maybe more, and we handle it differently along the way. But what I found is that it is not maneuvered alone. I was mistaken to think it is a journey taken by a lone man in a storm looking for any port. It is not a journey taken among the sea’s storms but rather a climb up the mountain. I thought we sought safe harbor to elude the storm, only to face it again. But no, I was wrong. That beast that controls the tides and evades our chase is not our realization or our present setting. We are not castaways at sea but rather men and women climbing that majestic formation of rock. Along the way, we face trials and hardships, unbearable conditions, and fatigue, but we are together in this ascent. We are bound as one with support from those around us and those we have never known. Our grief and anguish are not faced alone. No matter how we cope, how we believe it should be faced, or how it impacts us, we face it all hand in hand, climbing together. It is a struggle we often feel we cannot beat, thinking we are unchaperoned in our labor. But support is closer than we think, whether behind, beside, or a step away. This struggle is not singular, not separate, not alone, and never apart.